The traditional admissions calendar has been splintering for years and the current cycle has taken the process a few steps closer to a rolling calendar. We’ve argued previously that a multi-stage admissions process – one with multiple decision dates instead of a single May 1 date – empowers students in their college search, so this evolution helps them gain market power in the admissions market.

Despite the way it strengthens students’ hands, colleges are helping the transition to a multi-stage calendar. While lightly selective schools must be flexible with their schedule to make sure and fill their seats, highly selective schools with considerable cachet have also opted into a multi-stage process with more than one admission date.

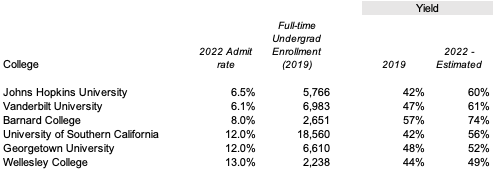

We’ll start by looking at a set of highly-selective colleges with unexpectedly-high targeted yields in 2022 to better understand their motivation, which we believe is at least partly an attempt to reconcile the natural tension between admission rates and yield, among other benefits.

Ivy+ yields

Putting yourself in the shoes of a college enrollment lead, if your college’s application numbers soar and you know your colleagues at other institutions are also seeing big increases, do you assume a yield higher than your past results? Logically, no. But in fact several Ivy+ colleges did just that in 2022. Crunching some preliminary numbers, we see that this year several highly selective colleges counterintuitively show a targeted yield significantly higher than their pre-COVID 2019 figures.

The obvious reason is their increased reliance on the Early Decision round. And that is true for several of the schools — but not all, as they use a variety of approaches.

Earlier Decisions

Early Decision is wonderful for a college’s yield but of course typically increases that other key metric, the admissions rate. To balance out relying on Early Decision, you need as many Regular Decision applications as possible. The logical – if not fully above board – incentive is to solicit, receive – and reject – as many of Regular Decision applications as possible.

Many enrollment professionals are genuinely uncomfortable with this dynamic, but it well describes the conflicting and cold-blooded incentives. The colleges are in fact cagey about releasing information on Early Decision, likely because it shows just how foolhardy applying in the Regular Decision round truly is. The most comprehensive data reporting on the round in the set of six schools listed above comes from Barnard, a college which has become more transparent about its two admissions rounds in the last couple of years. Using Barnard’s currently released statistics, we can calculate that the Regular Decision round this year had a 5% admit rate. How many students would apply to Barnard Regular Decision if they knew their odds were so low?

Besides Barnard, three of the schools in the table above lean on the Early Decision round heavily: Johns Hopkins, Vanderbilt and Wellesley. Johns Hopkins and Vanderbilt both accepted 5% of applicants in this cycle’s regular decision round while Wellesley hasn’t yet provided enough data to make this calculation. Barnard, Vanderbilt and Johns Hopkins have disclosed enough information to know that over half their entering classes were admitted Early Decision:

Georgetown & USC

Leaning on Early Decision and then encouraging – and rejecting – a large number of Regular Decision candidates is one way to game the naturally-conflicting yield and admit rates. But two of the other universities in the chart don’t have Early Decision rounds at all:

Georgetown: Georgetown instead leans on Early Action, where it received almost 9,000 applications this year. That’s a lot of students and the large number allowed the school to admit them at a rate below the Regular Decision rate. Georgetown can also defer many Early Action applicants to the regular round and then accept them, knowing that the yield on this pool will be pretty good, given the interest they have shown. With the need to enroll roughly 1,600 first years each cycle, this Early Action pool gives them about 900 qualified students to whom they can market and promote the school heavily. Instead of sprinkling recruiting efforts across thousands of high schools, they have a focused list of candidates. It functions like a marketing funnel and helps Georgetown achieve their impressive total yield.

USC: USC has only one Regular Decision round, but it defers thousands of students to the spring term, admitting selected students to the fall term on an as-needed basis. This somewhat unusual approach has several uses, including potentially serving as a way - we are speculating here - for the school to optimize revenues. USC is need-blind per policy but picking students off of a deferred admissions list may make that policy flexible. (USC is not a part of the 568 Group and so is not functioning under any legal commitment to act as a need-blind institution.) Besides any possible financial advantage, the deferral of many students to the spring term allows USC to admit relatively few students into the fall term. And the use of the spring deferral, which is unusual, muddies the waters: when exactly is a spring term acceptee invited into the fall cohort and how does it play into the admissions and yield percentages and other IPEDS numbers? Whatever the motivation, USC’s practice is a major step away from a unified May 1 acceptance date and likely helps the university achieve both admissions and yield targets.

So we have a situation in which six institutions with considerable market power and many qualified applicants are admitting heavily outside the traditional unitary May 1 window in a way that seems influenced by application and yield performance metrics.

Summers no longer off

In the olden times, college administrative staff could take it easy in the summer. No longer. If Early Decision and Early Action shift students’ attendance decision to earlier in the academic year, a set of additional factors are pushing decision points into the summer. The factors also further weaken the commitments - already muddied by confusing exceptions related to wait lists - students make when they accept an offer and make a deposit.

Summer poaching: The 2019 consent decree between the National Association of College Admissions Counsellors (NACAC) and the Department of Justice prompted speculation that colleges would, to fill out their class ranks in the later part of the cycle, begin poaching students planning on attending elsewhere. We are beginning to see anecdotal evidence of this occurring.

The removal of NACAC’s formal restriction will we believe inevitably lead to “summer poaching” becoming common. A school that accepts a student often hears nothing -- or almost nothing - back. It has little information about that student. So colleges with incomplete student quotas will, without any intent to poach, regularly contact students who may have already deposited elsewhere, encouraging them to enroll.

In a situation where even professionals can’t seem to get the rules around Early Decision straight, practices around depositing, double depositing and institutional collegiality will all dissolve into a cloud governed by consumer wishes and schools’ market power. We don’t see any impediment to this developing.

How firm is a “commitment”?: For now, poaching anecdotes concern students admitted by these colleges. The next level will involve contacting rejected applicants and maybe some social media fueled board of applicants who haven’t fully mentally committed anywhere. We stressed the growing “fluidity” of the calendar but “fluidity” also exists in terms of commitment, right? A student could be planning on going to a given college but maybe could be persuaded to change their mind over the summer.

No deadline for acceptance: Another trend complicating college summer schedules are universities without deposit requirements of any kind. Ohio University is a regional public university with a full-time enrollment of about 20,000 students, concentrated in its Athens campus but spread out over a branch network. OU is about as selective as quite a few state flagship universities (2019 admit rate: 82%) but requires only an online form without any deposit payment to signify intent to matriculate. Other colleges surely have similar policies. If you are a lightly-selective college, an open schedule helps you fill your seats and even boosts your yield – an applicant suddenly applying in July is a good bet to attend. Practices like this blur the boundaries between open-enrollment programs and those with an application process. Given the rising admit rates shown by many colleges, among them large public universities, we expect the number of schools within this zone of practice to expand. As it expands, it gives students more opportunities to walk away from any prior commitments on a dime.

The confluence of an oversupply of college seats, the fact that colleges don’t know students’ college plans and can contact them innocently if they have seats to fill, and the fact that students can change their mind about where to attend at any point before showing up on campus leads naturally – and it looks inevitably – to recruiting intensifying during the summer months.

Thoughts

Both students and colleges are taking actions that weaken the traditional May 1 deadline calendar as it changes from a single step process to a multi-stage, almost rolling process. Making predictions about how all of this will evolve is difficult, but there surely will be unforeseen consequences.

When looking at highly-selective colleges, applicants really need to know and consider the Regular Decision acceptance rate, not just the overall average. The single number usually featured isn’t particularly informative in the case of schools like Barnard (Early Decision admit rate: 29%; Regular Decision admit rate: 5%) or Vanderbilt and Wellesley (Early Decision admit rate is a multiple of the Regular Decision rate).

The impact of management metrics is unpredictable. In highly competitive situations like undergraduate recruiting, metrics will be gamed relentlessly and ingeniously. The six Ivy+ schools briefly examined here seem to have at least partly structured their application process so as to ease the natural tension between admit and yield rates.

Students should request waivers of application fees everywhere. (There should be an app to do this for you!) An application fee is like paying a barfly to let you pour them a beer.

Without formal barriers to “summer poaching” in place, the main impediment it faces may be that many college-going students want their destination settled in their last few months of high school. If that’s right, the college search calendar of the future will for most students be based on consumer preference, not policy and rules.

Find more information at the CTAS site. CTAS provides data, reports and personalized assistance with college pricing and aid appeals.