2022 Admissions: Plunging admit rates

The current cycle, Part II: The Ivies go asymptotic and more

With more and more applications and a mostly fixed number of seats, admission rates at the more selective schools are declining. This admissions tightening affects a sizable group of students – almost 250,000 incoming undergraduates enrolled in a school admitting under 35% of applicants in 2019, right before COVID. With parents, siblings, relatives, fellow students, teachers and counsellors all involved, you have an applications vortex that sucks in a few million people across the country each year. And this admissions vortex – the Instagram commitment sites, high schools publicizing acceptances, the almost obsessive media focus on who gets into Harvard and Princeton et al – seemingly intensifies each year, despite how US high school graduation class sizes are close to static year over year and total college attendance overall has slipped. This strengthening isn’t just a subjective impression; it’s in the data.

Between the Great Recession and COVID, the number of students entering a selective college each year remained roughly constant.

This flat enrollment can be seen quite high up in the selectivity spectrum. About the same number of students studied at colleges admitting between 20% and 35% of applicants in 2008 and in 2019.

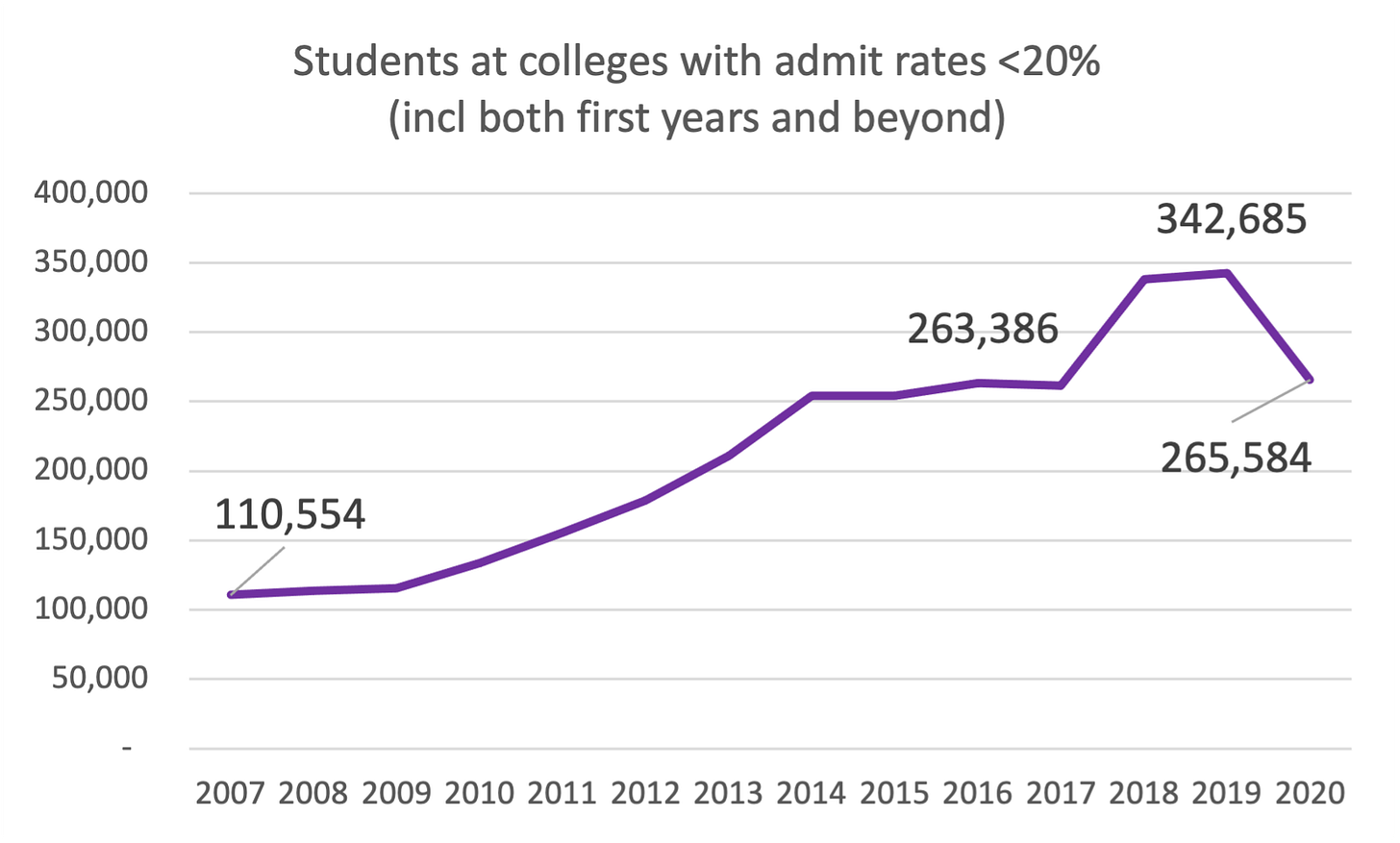

But enrollment at highly selective schools - those admitting under 20% - tripled between 2007 and 2019, the year before COVID, and is certain to be even higher this fall.

These schools have not been enlarging their programs much. Instead, more programs are becoming highly selective. So we have a situation where a business line - full-time largely traditional 4-year college - shows flat overall demand but, within the segment, the most desirable of the programs are receiving dramatically more student interest than even fifteen years ago.

Something is going on and what that “something” is calls for incisive social commentary. We can’t provide that commentary but we what we can do is look at some of the shifts, tabulating what is happening with Ivy League admissions, then turning to interesting developments in the “Ivy+” highly selective sector and then at some colleges outside the northeast and California “hot zones”.

Please note that the admission rates used here, released piecemeal in the middle of the admissions seasons, will tend to be lower than the final numbers as students get late acceptances. Comparisons with previous years official reported figures are not strictly apples to apples.

The Ivy League goes asymptotic

In 1940, Harvard accepted 85% of its applicants. In 1970, the University of Pennsylvania accepted 70% of applicants. A mere thirty years ago, Columbia accepted roughly a third of its applicants. These historical facts seem to originate from a strange, distant land.

As of right now, Cornell, the largest Ivy League school, is the easiest to get into with an admissions rate of 7.0% and Harvard the hardest, with a 3.2% admit rate. (We are including MIT in this tally. Princeton has decided to stop disclosing its rate in press releases.) This already highly selective group has an admit rate lower by an average 3% than 2 years ago.

Admit rates in the 1-2% range may lie in our near future. While this seems unthinkable to some US adults, it would put the Ivy League on par with the acceptance rate for Tsinghua University in Beijing, maybe the most prestigious college in China, which has an acceptance rate hovering in the 2% range. India’s leading university, IITB (the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay), likewise has an acceptance rate reputedly in the 2% range, although that figure is not comparable to US stats because an important national test imposes a first cut (making IITB even more competitive than the 2% figure indicates). A 1-2% level for the Ivy League and a few other universities is not unbelievable by world standards.

India and China of course are much more populous than the US, and Tsinghua and IITB, while they are sizable programs, don’t enroll as many students as the Ivy Leagues and peer institutions, so there may be demographic limits stopping every one of the most highly-selective schools from seeing much more tightening. But there’s no reason why Harvard’s acceptance rate couldn’t drop below 2% in the next few years – in fact, it would be somewhat surprising if it didn’t. The same can be said of Stanford, Princeton and Yale. Columbia and MIT are already trending downwards into that region. So the real question is how selective schools like Dartmouth and Brown will become. Whatever the exact number, ambitious students increasingly can’t plan on being able to attend an Ivy.

“Ivy+”? When you admit one-tenth of applicants, the shoe fits

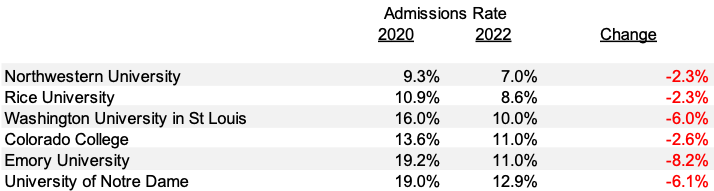

In 2020, a group of prestigious schools, such as Williams and Georgetown, admitted 15-20% of applicants. Virtually all these schools, sometimes referred to as Ivy+, now admit in the 9-14% range, just two years later.

The tightening at Tufts, Emory and Wellesley is extreme. The two schools that did not fall into the new and lower range are both smaller liberal arts colleges: Davidson College, which notched a pretty good admissions rate decrease to 17% (is “good” the right word?) and Pitzer, which we’d commented in our previous post on the 2022 cycle, actually became less competitive.

A category is born – big AND highly selective

Three of the universities in this “Ivy+” group, USC, UC Berkeley and Boston University, stand out because of their size. We’ll add UCLA to this category as well because, though its data isn’t yet out, it will almost certainly see a sharp reduction in its admit rate. Cornell University serves as a forerunner. With close to 15,000 undergrads, it is comparable to these institutions and has for several years been the biggest highly-selective school.

High selectivity has in the past been associated with smaller student bodies. If you glance at the chart at the end of this post, almost all the schools have undergraduate programs under 8,000 students. But the five universities above run large programs and, with the current application wave, they now conduct stringent admissions programs with many, many applications evaluated. We now have universities like Berkeley and UCLA, which enroll well over 6,000 new first years each fall, accepting only 1 in 10 candidates. Such a scale and volume represents a new frontier for enrollment management.

Their enrollment teams face a significant operational challenge and it’s not at all clear they can meet it without resorting to quasi-automated processes heavily reliant on quantified assessments, perhaps with the extensive involvement of enrollment consultants like EAB and Ruffalo. Berkeley and UCLA are particularly challenged because public universities have much thinner enrollment offices on a per student basis. Eliminating simple mistakes – like admitting a student you meant to reject – forms a task in and of itself, and ensuring the uniform application of admissions criteria - quality control - becomes very difficult.

The lesson for students as they enter these situations is that, despite how much emotion they carry into their college search, they are operating in an overloaded system where both simple and complex admissions mistakes will occur, where the standards used by the larger colleges per force must be impersonal, and where admissions decisions will pretty frequently perceived as unfair, unpredictable and somewhat chaotic. They can’t take any of this personally. (Don’t laugh.)

The admissions surge spilleth over

Much of our coverage of this cycle has focused in on the northeast and California. Is this surge in applications being felt elsewhere in the country? It is. Higher education in the Rocky Mountains, Texas and in the Midwest is focused on public institutions but the very selective private schools operating there are seeing more applications and tightening admissions.

To focus on one of these, Colorado College in Colorado Springs saw an increase of selectivity commensurate with other schools. One of only four private colleges of size in the state, it recruits nationally, with big portions of its student body coming from California, Illinois, Massachusetts and New York State, and this recruiting footprint carries over into its admissions rate. Already selective, it saw tightening in line with many east and west coast peers and looks very much like several New England liberal arts institutions purely based on metrics.

Others in these regions are converging to a more selective level. Washington University (St Louis), Emory and Notre Dame, in the past been less difficult to get into than Colorado College, saw some of the steepest declines in admission rates. Quality programs outside the northeast/California area which were slightly less selective than the list above have also seen sharply more applications. Both Georgia Tech and Case Western, for example, have materially tightened their admissions rates in the midst of very successful recruiting cycles.

The picture that emerges is of an overflowing number of applications nationally spilling over to reputable schools which, due to their locations, had simply seen a moderated number of applications in years past. It’s as if students were “arbitraging” the perhaps atypically loose admissions standards of Wash U, Emory and Notre Dame down to national levels.

In the next installment on the current cycle, we will focus in on four schools with particularly notable applications surges, Northeastern, Macalester, Colgate and, maybe the most remarkable riser, Florida State, to see if there are some common threads among these “hot” colleges.

Find more information at the CTAS site. CTAS provides data, reports and personalized assistance with college pricing and aid appeals.

The University of Pennsylvania admit rate was changed since the email distribution. The current number (6.0%) is based on an unconfirmed informal report.