The 2023 Admissions Cycle, Part I

Some colleges saw application surges but the crazy increases in 2021 and 2022 mostly disappeared

The headline news from 2023’s admissions cycle is that the COVID-era surge in applications has mostly abated. While some colleges did see large increases in applicants and, hence, their level of selectivity, for the most part, many selective schools saw either slight decreases or stable levels of student interest. We plan on covering developments in the University of California system separately. In this post, we’ll look at some of the winners and a few of the losers in the remainder of the country to flesh out some trends.

Mid-selective no more

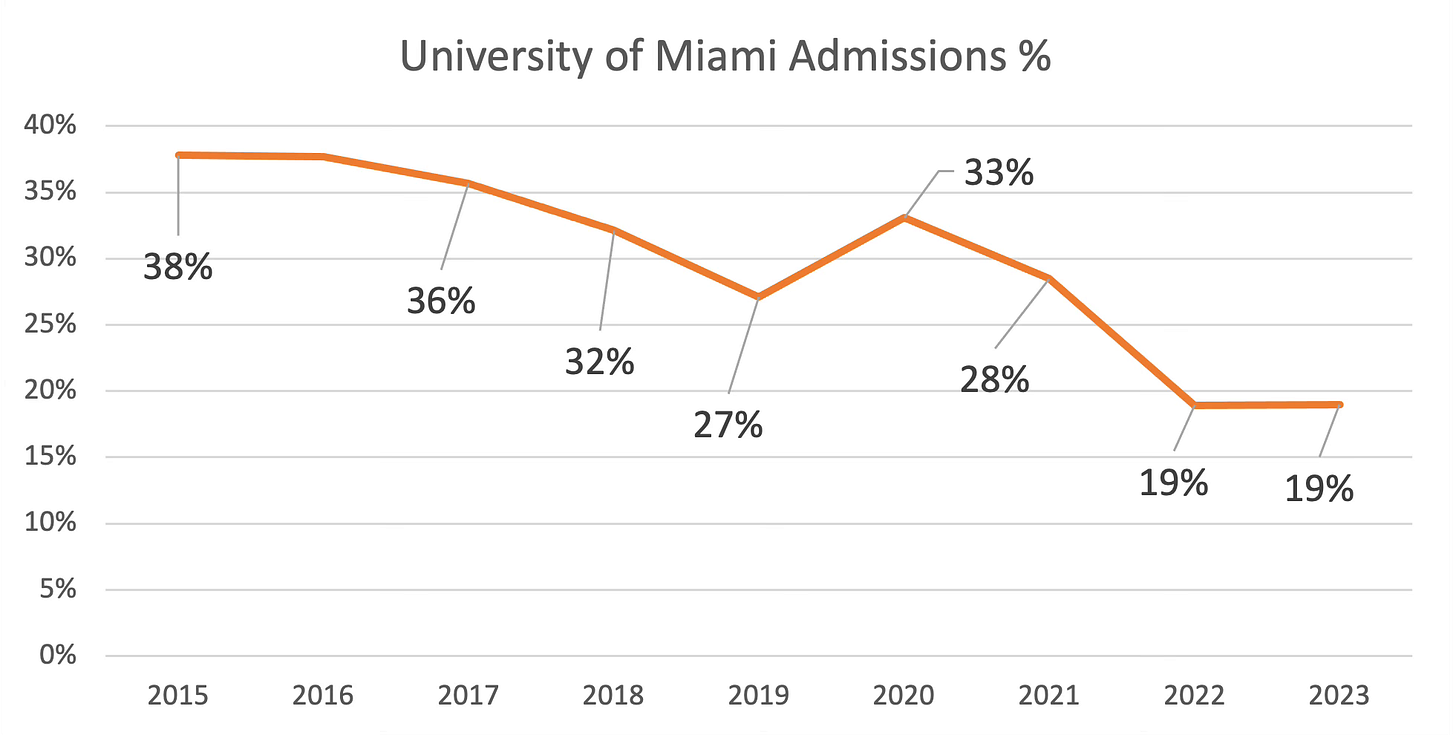

One emerging question in the higher ed enrollment market has been: whither colleges with 30-40% area acceptance rates? This question relates to a group of generally private mid-size colleges which traditionally were not “automatic ins” but had reasonable levels of competition for spots. In the bifurcated higher ed market – with a minority of institutions seeing large increases in applications while the majority of schools face increasing and sometimes brutal competition for students – which way would schools in this tier go? Up or down? There’s no definitive answer just yet but, for three private universities, the 2022 and 2023 cycles point to a future where they become highly selective.

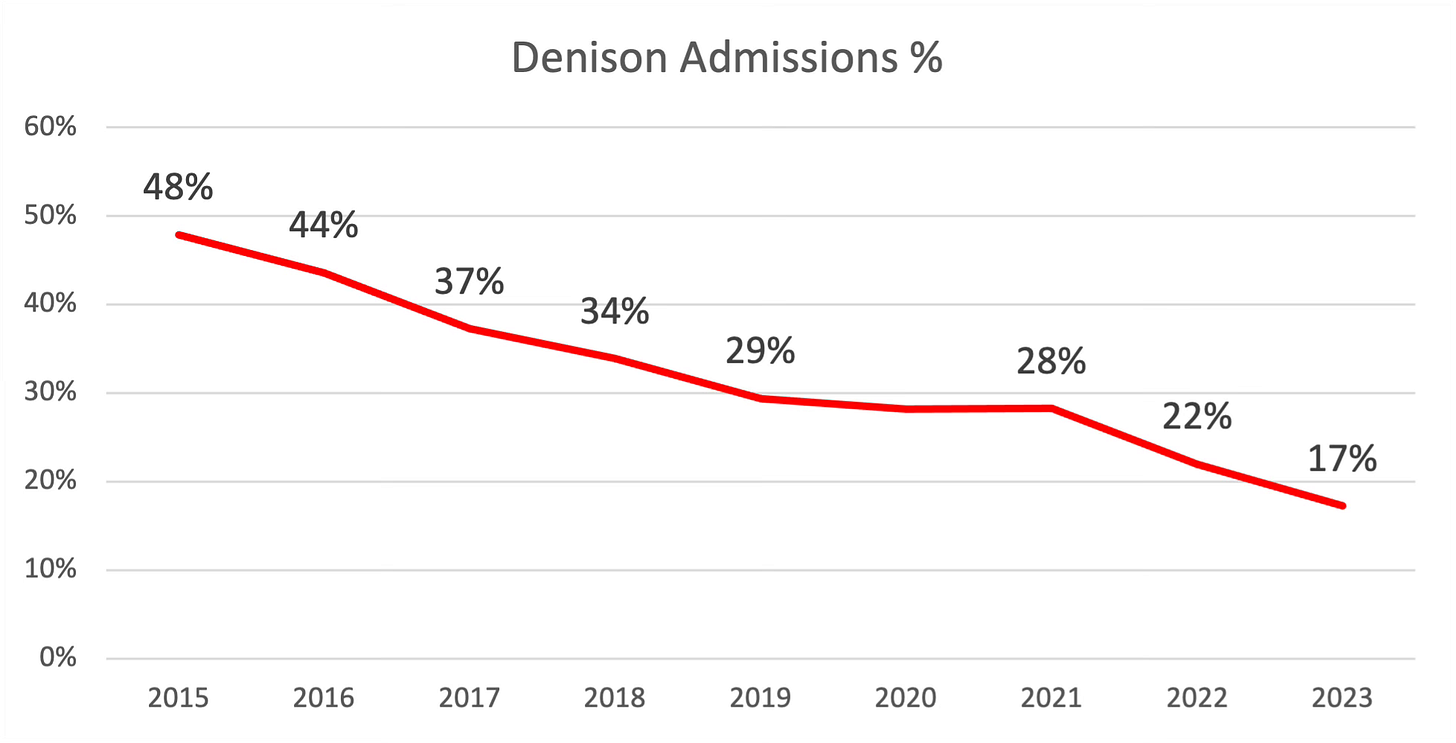

The first – and maybe most surprising -- entrant is Denison University. Located east of Columbus, in Granville, Ohio, this is a smaller program than the two others we will be spotlighting. In our blogs about the 2022 application cycle, we’d highlighted Colgate University as one currently hot institution. Denison is roughly comparable to Colgate in size and like it is located in a small college town. It also no doubt benefits from Columbus’ high population growth. The transformation from a middling selective college to one that accepts just 17% of applicants, as it did this past application cycle, is pretty remarkable.

This sharp increase in popularity has had financial benefits, allowing Denison to raise its prices through 2019, the most recent date where we have sufficient data, at a rate well above college price inflation.

In the period shown in this chart, Denison was able to raise its prices by 5.4% annually on a cumulative basis, far above nationwide undergraduate cost inflation rate and significantly outpacing even schools like Northeastern and NYU, known for their ambitious recruiting and high prices.

Denison has certainly been helped in all this by a generous $1 billion endowment, which is considerably larger on a per student basis then our two other “mid-selective” risers, Villanova and the University of Miami.

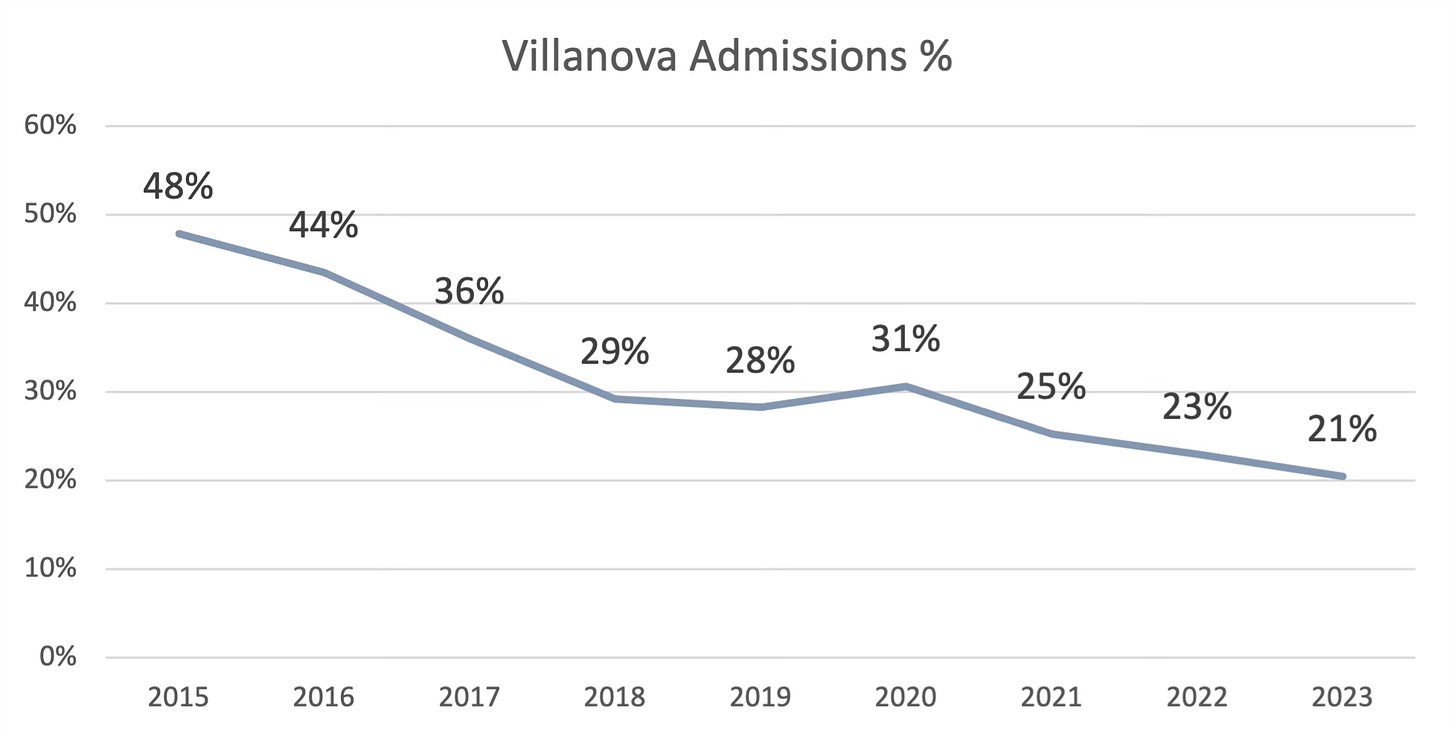

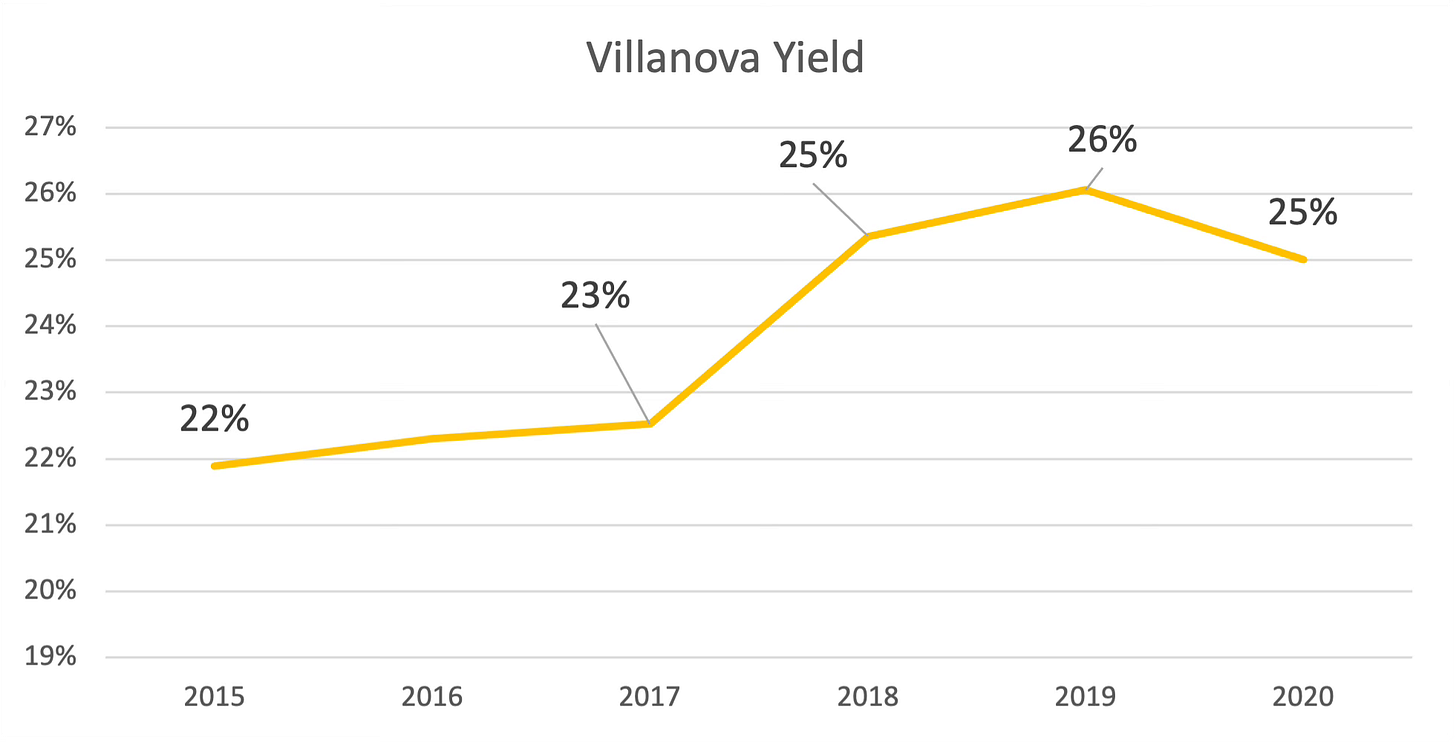

Villanova’s increase in selectivity is as spectacular as Denison’s, especially given the Pennsylvania program’s larger size. Unusually, it has been increasing its selectivity without seeing a surge in applications. While applications have risen a bit since 2017, it’s a marginal change. So how have they been filling their incoming class spots? With better yield:

Because of the narrowing funnel, small increases in yield can make up for large decreases in selectivity. At play are about 300 fewer students per class not admitted due to tighter admissions, a group of rejected applicants offset by about 300 more students persuaded to enroll out of the pool of admits. The jump in 2018 exactly coincides with Villanova’s initiation of its Early Decision option, so the proximate cause is pretty clear, although the contemporaneous success of its men’s basketball team is almost certainly another driver.

Most businesses would take the increase in interested students to boost the size of their institution and its revenue streams. Not Villanova, up until recently. This reluctance to increase their class sizes shows how a university like Villanova has both a different mindset from most other organizations – even many non-profits jump at the chance to increase their scope with a rise in revenues – and the way in which higher ed is constrained by the physical plant capacity demanded by more students. Articles such as this 2022 story don’t even ask whether the university should expand and this second one from the campus newspaper drily states without explanation: “The ability to host 21% more students is not feasible, and thus the University must commit to a lower acceptance rate compared to the application rate.”

The area’s high housing prices and nonexistent undeveloped land is likely the cause of Villanova’s inability to expand. But over the summer, after being approached by the smaller school, Villanova moved to take over the campus of nearby Cabrini University, a failing Catholic institution that owns over 100 acres of land in a pricy suburb. Though plans for the campus are still uncertain, Villanova appears uninterested in Cabrini’s educational programs or faculty. The merger will certainly give Villanova some opportunity to increase overall enrollment, whether at the undergraduate or graduate levels. It looks similar in nature to Montclair State’s takeover of struggling Bloomfield College in New Jersey and, to an extent, neighboring St. Joseph’s University assumption of the University of the Sciences, also in the Philadelphia area. All of these mergers took place in geography with few opportunities to expand footprints.

Likewise, Miami is growing and in 2022 initiated new construction of a dorm and other facilities. The university is a bit cagey about whether this new dorm will lead to more undergraduate enrollment, but construction trade news items imply it. The picture that emerges here is of universities wanting to expand their program headcount but facing very real constraints – and those constraints are real estate, which takes a lot of time to design and build even if the land is available. We can also point to what may be an emerging trend: amidst a demographic decline in high school graduates, certain very successful schools look like they’re beginning to think of expanding their programs, which will put further pressure on struggling competitors.

Minor selectivity declines at certain “rejectives”

While a university like Denison is thriving, some “highly rejective” institutions saw minor declines in applications. For example, Harvard saw a drop in applications to slightly below its 2021 total. But of course this drop needs to be put in historic context; it is still much more difficult to gain admission there than right before COVID hit.

A similar pattern of minor drops in application totals was experienced by a variety of very successful institutions, including Dartmouth, Georgetown, Pitzer and UCLA, but these came off dramatic rises in the preceding cycles.

One admissions office that probably welcomed the decrease was MIT. MIT of course resumed requiring board scores this cycle and we speculated that this was specifically intended to cut down on the number of applications sent in. After all, rejecting applicants is not a core function of a college. Well, MIT: mission accomplished!

MIT is still receiving thousands more applications than before it went test optional but, assuming we are correct about its intent, this is no doubt a step in the right direction.

None of these institutions was at all threatened by these small drops, but three highly selective schools did report significantly lower applications. In part 2 of this survey, we will dive into these three situations, which have different meanings and reveal different things about the higher ed recruitment landscape.

Up next in Part 2:

Application declines: the real and the accounting-driven

NYU and Northeastern

… and some concluding thoughts

CTAS provides support for families and professionals on topics like college financial aid, pricing, funding and planning. Don’t hope the financial aid awards you receive are satisfactory. Take control of the situation and “shop for college.”

The best “quick glance” into our profession. Thanks so much!!