Undergraduate pricing trends in the 2010s

The impact of family income, enrollment mix and weakening college pricing power

The 2010s began in the midst of a deep recession, with the economy gradually recovering after 2012. Undergraduate pricing witnessed a sea change in terms of process and environment and in terms of dollars and cents. The present study lays the economic foundation for understanding the marketplace’s macro drivers. The longitudinal analysis that undergirds this report will lay the groundwork for future forecasting and trend analysis, with a customer-centric focus on student spending and enrollment patterns.

Major themes

Undergrad spending on college in the 2010s was tightly correlated with family income

Student spending on college in line with incomes

But the details of this article will show individual college pricing power is weak, with general student spending increases caused by changes in “Mix”

GDP, Inflation and Household Wealth fail statistical tests as drivers of college costs

Bigger is better… large 10,000+ student colleges lead sector with strong pricing power

Smaller colleges have been forced to cut prices amid falling enrollment, institutional closures

Highly selective institutions unsurprisingly show pricing strength

Public colleges show marginally greater ability to raise prices vs private, but off of a lower base

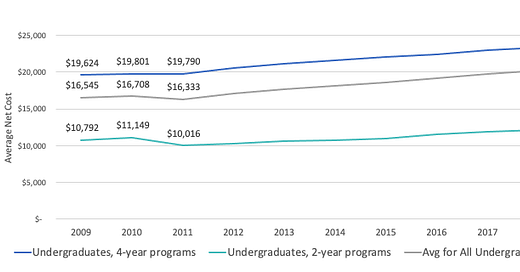

Slow price increases since the Great Recession

Average net cost* for US undergraduate programs rose at a 2.3% annual rate from 2010 through 2019**

Partly due to pricing increases by colleges

Partly the result of changes in “Mix”

Latter part of the decade (2014-19) showed net cost increases of 2.7% on a weighted basis

Increase in pricing power in 2014-19 allowed colleges to raise net costs by 1.5% annually, about half of the increase in student spending

* Net cost is a consumer-centric metric comparable to what cost means in business transactions outside of higher education. It represents a student’s cost of attending college including: tuition, room & board, fees and estimates of supplies less institutional aid of all kinds (including need-based and merit), and less federal and state/local aid. Loans and other repayable amounts are excluded and do not reduce the cost. Room and board uses on-campus costs; for students attending nonresidential institutions, the college's own estimate of such off-campus costs is used. Total average net cost for all students allocates in- and out-of-state costs in proportion to attendance. Net cost differs from the Net Price figure self-reported by colleges to the NCES because it is comprehensive and covers all students, including the approximately 40% not covered by Net Price calculations.

** All dollar figures are in nominal dollars. Results calculated using IPEDS data with proprietary analysis and adjustments. The calculation is not dependent on price variances dictated by student family income, but represent averages.

“Mix”: Change in the proportion of students attending institutions in different categories with different net costs.

Average net cost can change even with no change in individual college net costs as consumers buy cheaper or more expensive options.

In the 2010s, students shifted their spend to attend more 4-year and more selective colleges and away from less expensive options

Calculations of Mix always require some interpretation, but our analysis shows that about 2/3 of college cost increases in the decade are actual inflationary net cost increases and 1/3 are “Mix” changes with students choosing more expensive options.

Straight net cost increases for all colleges: 1.3% (2010-19)

This is a pure arithmetic average for all schools within a category and does not reflect attendance shifts between schools and categories.

This average includes both 2- and 4-year college so contains a “mix” impact as student preferences for 4-year schools over 2-year programs increased in the decade.

The fact that overall arithmetic average is higher than either of the two components below is counterintuitive but correct as students shift from a lower price options, such as 2-year colleges, to higher-priced 4-years.

Straight net cost increases by sector

1.1% annually for 4-year schools

0.3% for 2-year (both for the 2010-19 period)

Latter part of the decade (2014-19) showed an improving environment

Net cost increases of 2.7% on a weighted basisIncrease in pricing power in 2014-19 allowed colleges to raise net costs by 1.5% annually, about half of the overall increase in student spending

Certain sectors have bucked this general trend.

Public colleges able to raise net costs more successfully than private

Public: 2.6% annual increases 2010-2019, private only 1.4%

Private schools were forced to enact big price rebates in the aftermath of the Great Recession

Private schools act as the “swing price setter” and were particularly vulnerable in the Great Recession

Changes in proportion of students attending public and private colleges account for the overall average being slightly lower than the components. Mix impacts affect all of these percentage changes

Summary: Colleges have increased revenues by attracting more students. Overall, there is little ability to raise prices.

“Mix” changes: about 2/3 of 2.3% annual cost increases (2010-19)

College pricing power about 1/3 of this 2.3%

Straight net cost increases ran below Federal Reserve Consumer Price index increases of 1.8% for the period, intensifying institutional cost pressures. (Fed CPI index, 2010-2019)

Net cost, a measure of student spending on colleges, is not an exact proxy for undergraduate program revenues, but given flat or declining government appropriations and federal student loan borrowing, it is closely linked

Bigger is better

Average costs increase in line with college size

Large schools have been able to leverage their advantages both in terms of net costs and also enrollment (more about that later…)

Colleges with over 5,000 full-time undergrads showed above average price gains(>3%)

Small schools (<1,000 full-time enrollment) in contrast began the decade able to charge a few hundred dollars less than large schools on average (small: $17,601, big: $18,390)

By the end of the decade, that difference had exploded to almost $5,000 (small: $17,788, big: $23,516)

So small schools were unable to pass on any price increases through the decade

2-year colleges show decent pricing strength despite significant enrollment declines

Tuition & fees rose by 26% from an average of $3,711 (in 2009) to $4,482 (2018)

These tuition & fees include these items only and exclude room & board charges and estimates for nonresidential students and Title IV non-repayable aid, including Pell grants.

Selective colleges do the best

The more highly selective a college is, the more it has on average been successful at pushing through net cost increases

Colleges with admissions rates <20% enjoyed 4.5% annual price increases

Those with admissions rates <35% stood at 4.2%

The Ivy Leagues, Stanford & U of Chicago were comparatively restrained, charging 3.4% more annually

College spending remains tightly anchored to family income

Average net costs as a % of family income have held very steady in the 2010s, within 21-22% of Median Family Income

Avg Net Cost of a 4-year college as % of Median Family Income with at least one parent holding a Bachelor's The personal income benchmark used here is US Census Family Income for families with head of household older than 25 with at least one family member holding at least a Bachelor’s degree (includes those families with a graduate degree). This represents the prime market for undergraduate enrollment. Net costs are for 4-year programs.

Average for 2010-19: 21.5%

Low: 21.0% in 2017/18

High: 21.9% in 2010/11

2008/09 school year saw a high of 22.8%.

Source of Income figures: U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement, FINC-18.

A tightly-linked relationship between family income and college costs strongly suggests a market equilibrium for spending on higher ed exists

It is possible that the ratio is drifting down more recently amid solid personal income growth after 2012

So what? Isn’t this just data mining?

Correlations are strong for different spans of time

Correlation between % change in average net costs for undergraduate programs and family income (age >25, with college degree) growth is 0.80 for 2010-19 (maximum of 1.0)

This very high correlation is supported by a p-test of 0.06

For several different time periods in the decade the correlation is always above 0.55

An alternative comparative index is the Median Family Income for all families (all educational levels)

Avg Net Cost of College (all undergraduates) as % of Median Family Income of parents, all educational levels The 2010-2018 correlation level is 0.77, with a p-test of 0.01. Again, a strong social science stat result.

Correlations with Median Family income with parents who hold graduate degrees are good (0.65 for several periods) but weaker p-tests show a more uncertain relationship.

The relationships between the Family Income levels (total population and headed by someone with at least a Bachelor’s) also holds with more granular college cost indices. The comparisons above are made with college costs for all institutions (2- and 4-year). The index for 4-year colleges only shows high correlations for Median Family Income with at least a Bachelor’s of 0.87 (p-test of 0.06) (!) and for Median Families – Total Population, a correlation of 0.72 (p-test of 0.01). The key qualitative point here is that several widely-used US Census personal income benchmarks are clearly linked to college costs. Quantitatively-oriented readers may question the relationship but the links across related indices point to a real, existing economic equilibrium.

What college spending is NOT related to

Household wealth: The college-cost-to-income relationship is much stronger than the relationship with wealth or financial asset prices

Net household wealth grew 69% in the 2010s (source: Federal Reserve).

The chart below show the growth in net household wealth in absolute dollars indexed to 2009 (set as 100).

Inflation: Correlations between the % change in the Fed Consumer Price Index and the average net costs of college are negative with a p-test strongly indicating a null result. College pricing has not been related to inflation in the recent past.

GDP (specifically, nominal GDP, without inflation adjustments). Same result as Inflation: weak, often negative correlations.

The 21.5% ratio of average net costs to family income is a US industry average. For individual institutions, the ratio of their student body’s average family income to average net cost will vary.

Community colleges: 2-year program net costs also hold proportionally with median income of families with parents with an Associate degree, but the relationship is weaker. See the trend below, which also clearly displays the excellent value provided by the community college network.

How can knowing he relationship between net college costs and median family income be useful?

For Colleges

Pricing and discounting across an entering class will likely be closely linked to the median family income of a college’s average student (average in economic terms)

Does deviation from the 21.5% industry average for 4-year colleges signal an opportunity or a risk?

What is your college’s trend change in net cost to enrollees’ median family income?

Student family wealth (assets), academics and demographics will affect the cost to income ratio for individual students

But this doesn’t significantly affect the willingness of families to use these assets to pay for college

Do students & parents accept that wealth should have a role in setting college costs? Data suggests they do not.

Families don’t know what their Expected Family Contribution (EFC) is, don’t use it to budget for college and, based on the lack of a link between household wealth and college spending, don’t accept use of asset metrics in setting costs

Hence, it is not useful for colleges aside for administration of financial aid calculations

For Students and Families

The net cost to median income doesn’t show what the “right” proportion of spending is for individual families

It shows what the US market has decided is appropriate

Such benchmarks are always useful in evaluating your own budgets and plans

What are your fellow students doing? How do your plans compare?

Future pricing thoughts

The fallout from the Coronavirus on family income is hard to predict, but colleges need to keep an eye on the median family income levels to assess tuition revenue possibilities

US Census data collection on incomes is lagging and local changes are important to most colleges, making this assessment complex

CTAS will be issuing granular net cost, revenue and enrollment projections based on the paradigm summarized here

Will this 21.5% proportion between Family income (with Bachelor’s degree holder) and Average net cost see an inflection change in the future?

Why it might rise?

Need for education in a complex world

Long-term increases in income make education a more affordable investment

Why it might fall?

The COVID Recession puts a squeeze on personal income

Rising student debt levels among certain segments of recent college graduates indicate post-graduation outcomes are risky, with college not leading to a successful career for a fairly sizable minority of grads

Technological disruption (distance learning) lowers the cost and erases the capacity constraints associated with in-person teaching