How do we know whether a college is running an effective undergraduate program? Retention – the % of first-year students returning for a second – offers an up-to-date metric. While it isn’t the be-all-and-end-all - other measures and information are important in “grading a program” - retention offers a bottom-line result measuring whether students can do the course work, can afford to pay for the program and, finally, like what they are getting from the college. Because retention at different classes of institutions isn’t comparable, this series tries to decompose what retention is telling us about schools in a given category and region to allow for valid lessons.

In our prior post, we looked at how the Great Plains – stretching from Oklahoma City to the Twin Cities and extending into the Rockies to include Idaho and Montana private colleges – was a potential Ground Zero if any private college crisis materializes. The region shows drastic higher ed overcapacity with a subset of its schools failing to retain students at levels within the norm for US higher ed, putting them at risk of commercial failure.

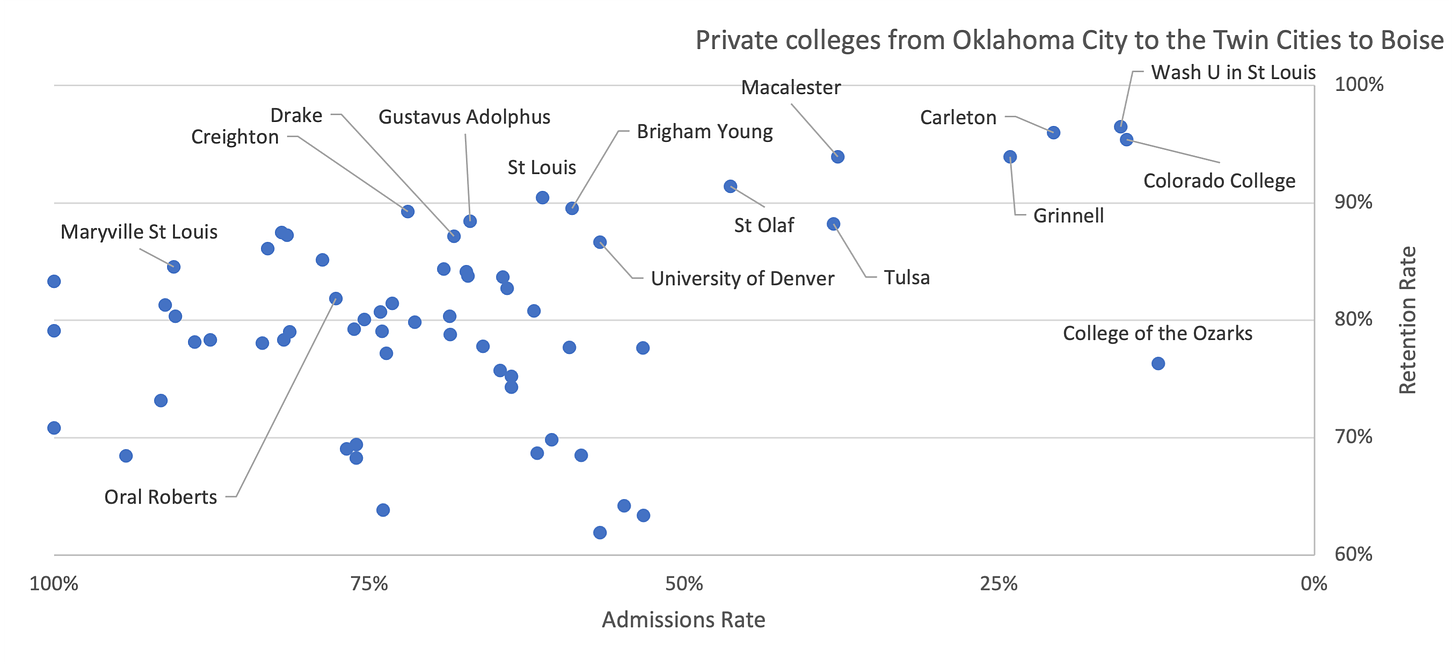

Happily, a larger contingent of Great Plains private institutions are doing just fine, thank you, with metrics that look a lot like colleges elsewhere in the country:

Readers of the e-mail can click on charts to see them magnified.

Four colleges in the region walk and talk like elite schools. Washington University in St Louis is the largest of these, with over 6,000 undergrads enrolled. Wash U is joined by three liberal arts colleges, all with enrollments of ~2,000 students: Grinnell, Carleton and Colorado College.

Macalester College in the Twin Cities, highlighted earlier as one of the current enrollment market’s winners, is close to matching these four along the retention/admissions matrix. (After hovering in the 40% admissions-rate range in recent times, its retention leads us to expect that Macalester will grow more selective and, sometime in the near future, admit under 25% of applicants.) All five in turn report retention just a bit shy of the levels seen in the Ivy League and comparable programs. These five colleges, recruiting from across the country, only loosely rely on their home area. The region’s many other programs remain more closely tied to dynamics in the Great Plains.

St. Louis and Creighton

Two of them jump out with very solid results. Both have similarities, fly under the radar, and reveal some of the region’s enrollment market peculiarities.

The first outperformer is St. Louis University. St. Louis doesn’t just fly under the radar, it almost operates in obscurity. Looking at the institution as a whole – from its efforts in the health sciences to a high-performing and pretty large undergraduate program (6,000 full-time students and a full-time equivalent count of 7,645 in 2019) – the lack of publicity is a bit perplexing. With consistently excellent retention results in the low 90% range and long-term support from the university’s significant and growing endowment, its undergrad program seems poised to continue thriving as a successful mid-size 4-year.

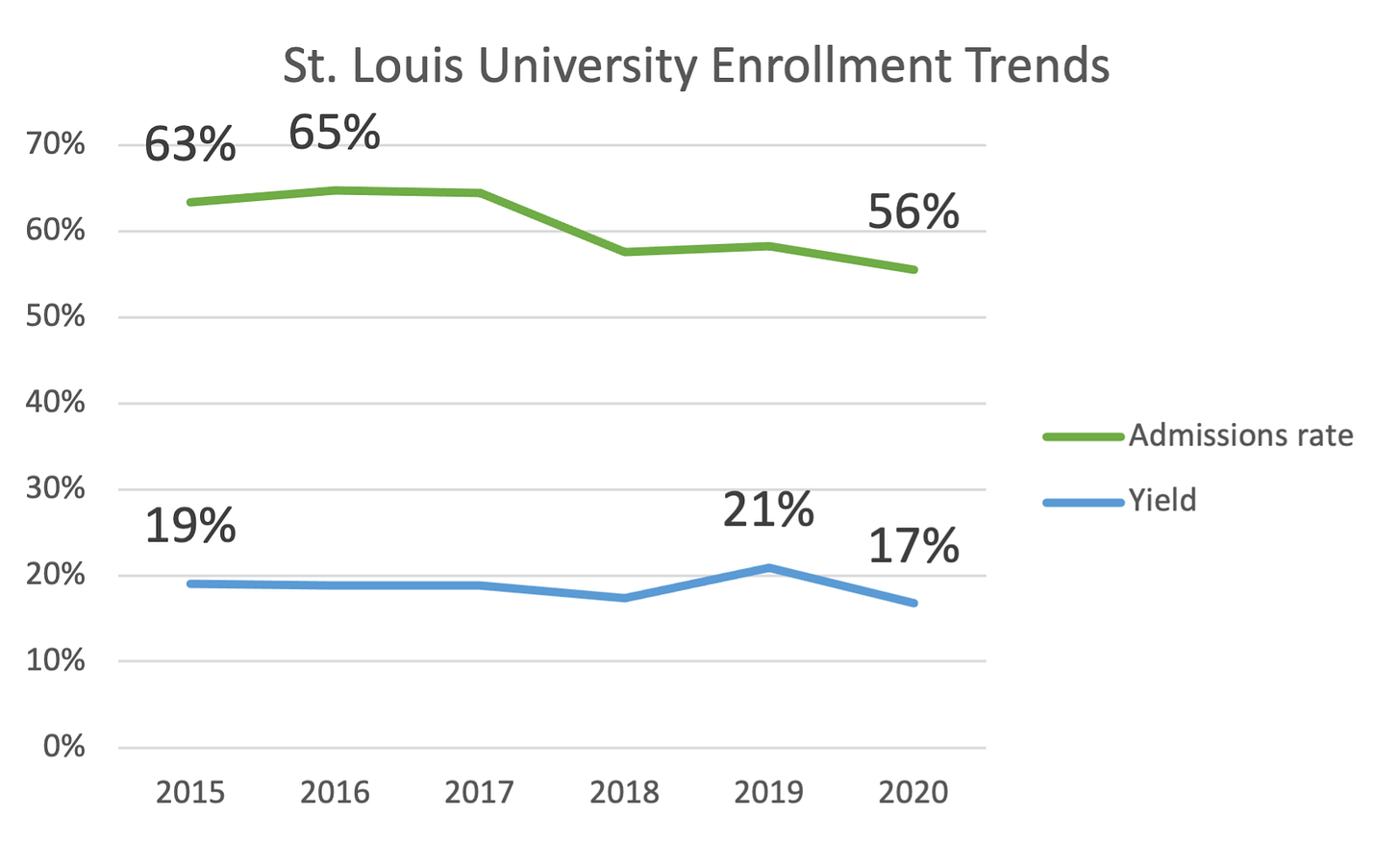

In terms of raw application totals, St. Louis has experienced a nice rebound, with 15,573 received in 2019 vs. a recent low of 12,772 in 2015. The rise in applications allowed it to tighten admit rates before COVID, although its largely-flat yield has not exhibited improvement.

St. Louis very much fits the mold of a private mid-tier university. A comparison with Elon University in North Carolina gives some insight into what St. Louis is achieving, despite the flat numbers. Six years ago in 2016, key enrollment statistics for the two universities were much the same. Close in selectivity, both could boast of very good retention with similarly sized undergrad programs. There were some differences – Elon had better yield while St. Louis had an endowment an order of magnitude larger – and one was suburban while the other was urban – but, all in all, they clearly were peers in similar situations.

Since 2015, Elon has been forced to loosen its selectivity and admitted close to 80% of applicants immediately before the pandemic. In contrast, St. Louis, as the graph shows, has upped its selectivity a bit. This underscores the difficult environment in which private colleges operate. Both schools run high-performing programs but only one of them – St. Louis - has managed to slightly improve its recruiting position.

Several other factors support St. Louis’ relative stability, besides the fact that it is running a successful and competent undergrad program. The university has increased its financial aid budget and worked to make the college even more affordable for middle class families: the average net cost was lower in 2019 than in 2015. And high schoolers in Illinois, just across the river, are going out of state for college in unusually large numbers. (In the 2018 cycle, St. Louis enrolled more students from Illinois – over a third of its entering class - than even from its home state of Missouri.). The university administration, who look to be hard working, are simultaneously rolling out multiple graduate program offerings and expanding a big health care complex, so the institution as a whole is thriving.

Whether St. Louis can use its strong undergraduate performance, significant financial capacity and general energy level to ascend the ladder and become a more selective private school with higher name recognition will depend on forces beyond its control – everything from the attractiveness of its metro area to whether Illinois high school students continue to leave their state in outsize numbers – but the institution is doing its part to get there.

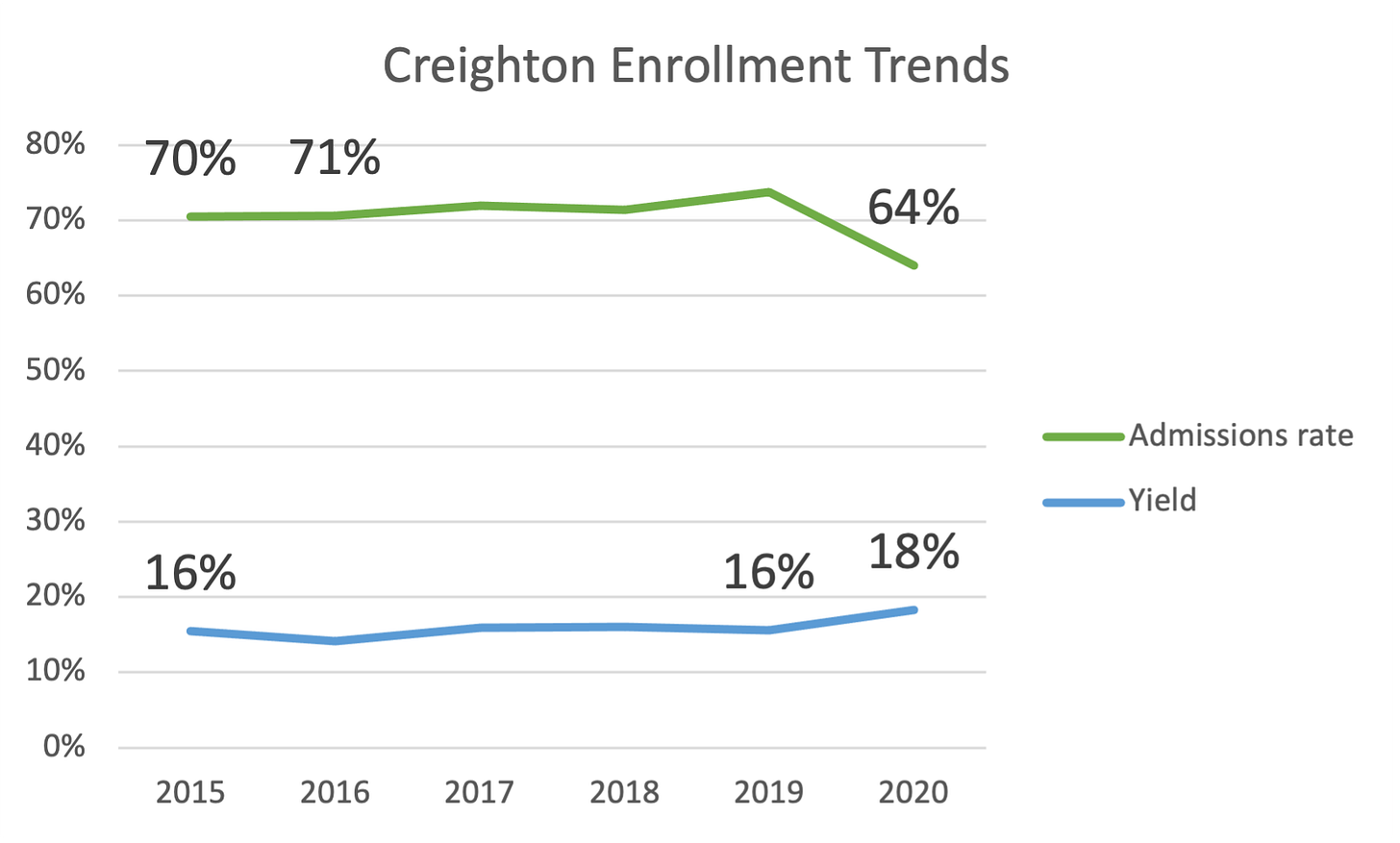

Creighton University is in many ways like St. Louis University at a slightly lower magnification level. Its undergrad program is somewhat smaller; in a metro area (Omaha) with about half of the St. Louis area’s population; Creighton is also bit less selective (74% acceptance rate in 2019) and has slightly inferior yield (hovering in the 14-16% range).

But both universities are aggressively expanding their health care centers and marketing their health care programs at both undergraduate and graduate levels. And both can boast of retention above what one would expect. Creighton boasts strong retention with stable results consistently sitting in the 89-90% range despite its light selectivity. Like St. Louis, the school is running a successful program.

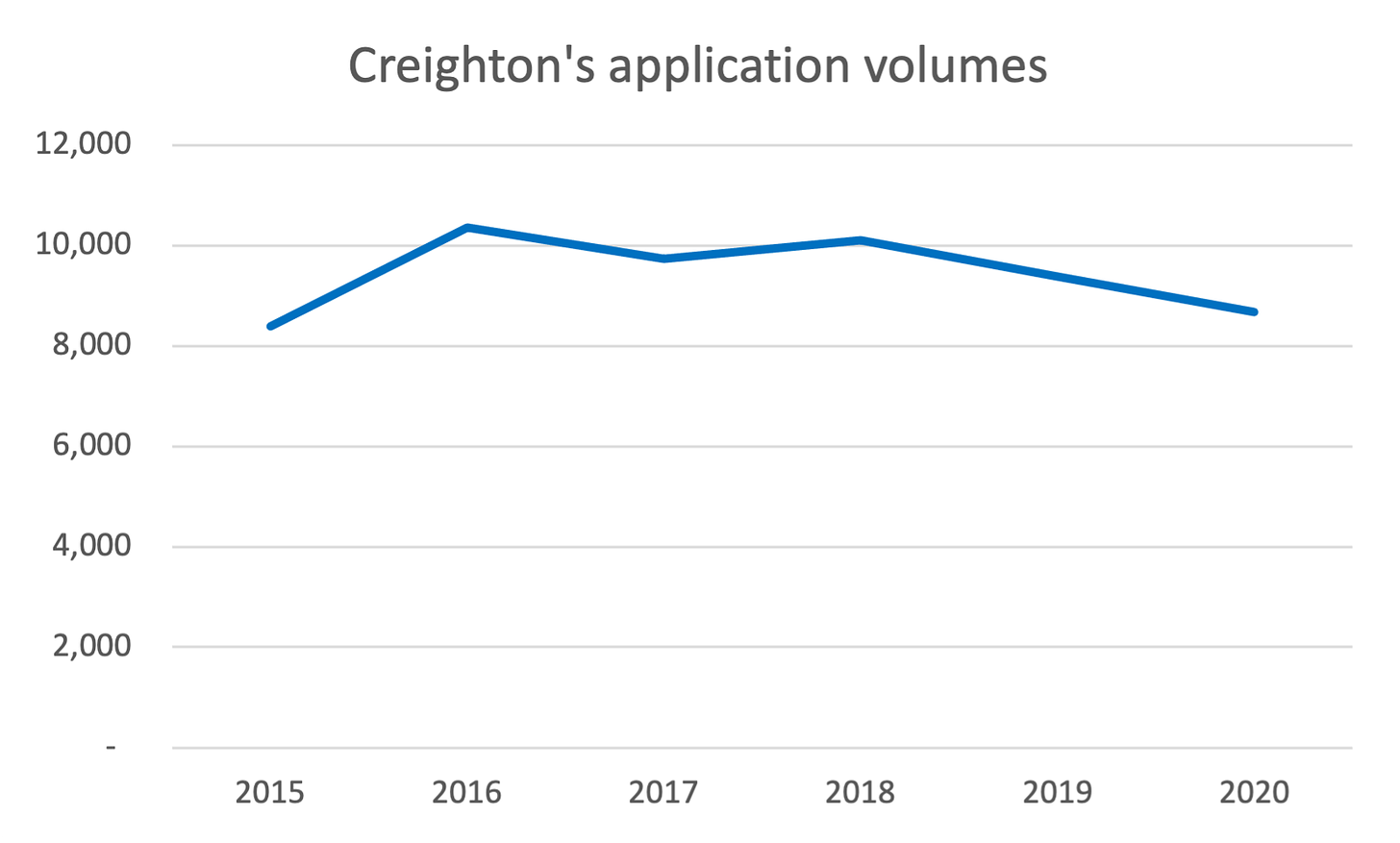

But this has not led to any uptick in applications:

Yield and admit rate are also flat if we ignore the unusual 2020 COVID admissions cycle.

In our look at California’s UC and Cal State network, we’d noted that even a slight overperformance in retention had propelled Cal Poly Pomona to a notable surge in applications. It became “hot” with retention rates similar to those from St. Louis and Creighton. So why haven’t our two Great Plains schools benefitted? Besides the fact that the entire category of somewhat selective larger private programs is facing some challenges - see the Elon comparison - we can’t know for sure. A couple of possibilities:

The oversupply of private college seats in nearby schools – colleges like Midland and Dubuque which we highlighted in the prior post on the Great Plains – may be dragging down the results for outperformers like Creighton and St. Louis. These two are failing to boost their yield in the face of competition from desperate small colleges, willing to cut prices and make all sorts of accommodations to enroll students.

Enrolling in college in the central plains isn’t particularly difficult. Most schools have acceptance rates above 60%. Compared with the competitive California application market, students will be spending less time on the application process, accessing relatively few educational consultants, and will be less aware of or interested in performance differences among college programs. It’s a more laid back scene.

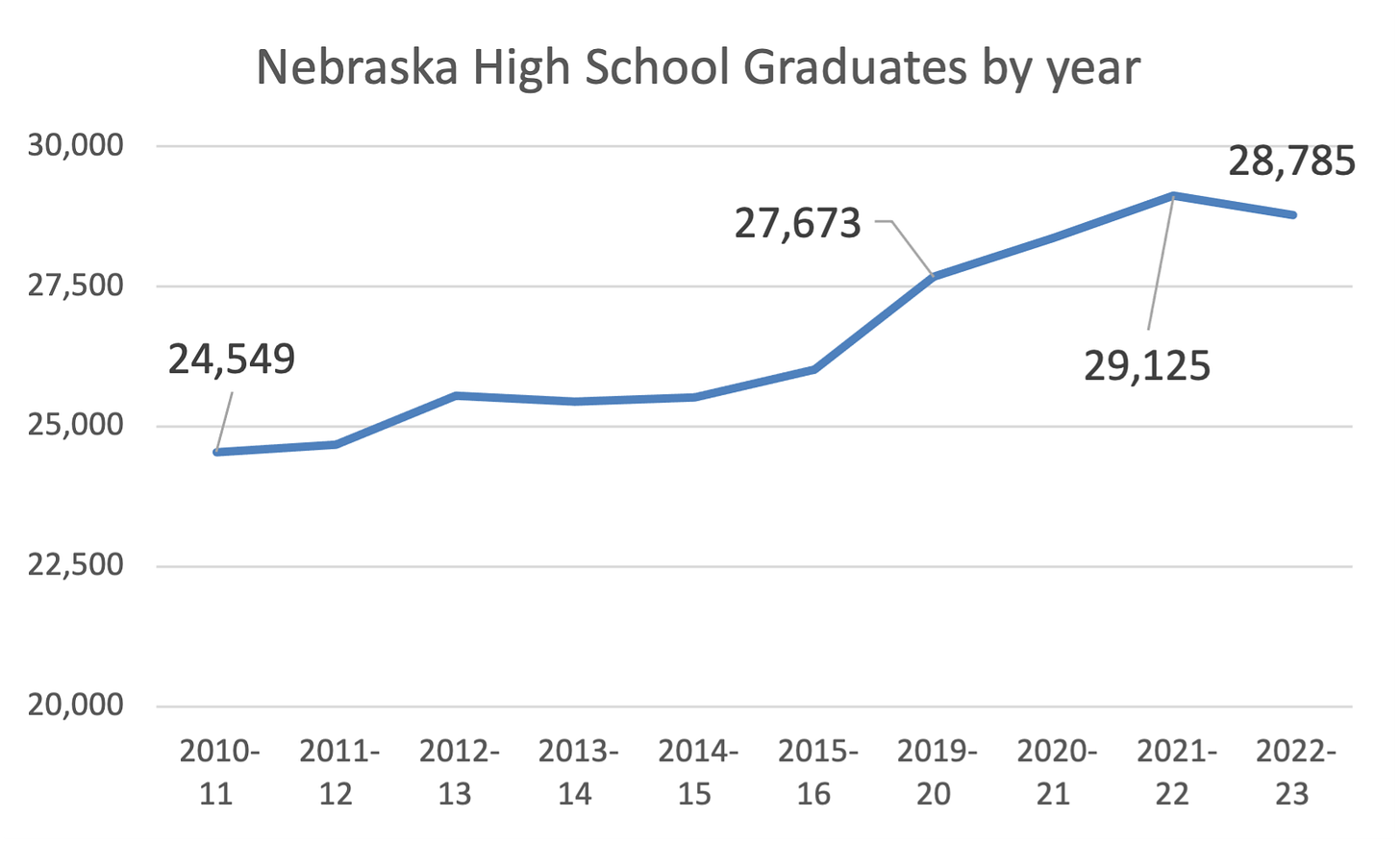

One possible cause that doesn’t hold water is unfavorable demographics. Both home states of these colleges, Nebraska and Missouri, are seeing stable high school graduating classes. Nebraska is in fact showing growth:

These two outperforming programs - to which St. Olaf’s, south of the Twin Cities, should be added with an honorable mention - show how educational quality is flourishing in the region while also highlighting how an oversupply of seats, even in a demographically-favorable environment, may prevent institutions from enjoying the kind of application booms seen in other parts of the nation.

The nation’s most unusual highly-selective college

One name stands out in the first chart above with abnormally low levels of retention: the College of the Ozarks, the biggest outlier among all of the US’ “hard to get into” schools. Located near Branson in the Ozarks lake region of southern Missouri, it is unique among colleges with low admissions rates because it loses almost a quarter of its entering class each year, far more than any other school with similar selectivity. Two explanations – which aren’t mutually exclusive - may cause this:

College of the Ozarks is an avowedly conservative, religious school. It routinely expels students who have sex or consume drugs or alcohol. Anecdotes point to many students enrolling, violating policy and then being asked to leave.

The College admits a much wider range of standardized test scores than comparable colleges. In 2018, the 25th percentile point for enrolled students was an SAT score of 1077 (both SAT and conformed ACT). In comparison, the 25th percentile at Wash U in St. Louis - which is actually a bit easier to get into — sat at 1422. 1077 is a very atypical 25th percentile score for a college as selective as the College. This combination of facts – very high selectivity, low retention and low test scores among a subset of entering students – hints at a mismatch in philosophy between the school’s enrollment and instructional wings.

Whatever the cause of students leaving, these departing students walk away with little debt. The school costs about as much as attending a community college full-time. In return, the College – “Hard Work U” – requires students to hold campus jobs during its demanding academic program. Frankly, asking students with test scores in the 1100 region to survive such a time-intensive calendar while taking classes with students with scores in the 1400-1500 region will lead to departures.

Rigid behavior standards, applicants with a wide range of board scores, a demanding work and academic schedule. The College of the Ozarks is… different.

The Great Plains is a region of contrasts. It boasts quite a few private programs with excellent retention, among which are a set with national reputations and very demanding admissions standards. These colleges sit side-by-side with a set running on fumes. That this situation hasn’t led to a wave of closures or mergers may be evidence of these weaker colleges’ resilience - or their obstinacy and lack of options. But whatever the reason for them keeping on keeping on, there is some evidence that the weaker schools are handicapping their stronger neighbors.

In the next installment, we will turn back west to look at retention in California’s non-profit private sector.

Find more information at the CTAS site. CTAS provides data, reports and personalized assistance with college pricing and aid appeals.