Too many college grads, but little enrollment impact

Individual and policy responses to the glut

In the preceding post, we had looked at the Federal Reserve’s tracking of underemployment among Bachelor’s degree holders, those working in roles mostly held by those without degrees. Roughly one third of all college graduates hold such non-college jobs, a proportion that has held steady for the last three decades. And these non-college jobs are unfortunately becoming less remunerative.

Drawing on Fed and US Census data, we had worked up a rough estimate that, of the 60 million holders of Bachelor’s degrees in the US workforce, 24 million held positions that either didn’t require a college degree or held ones that did require it but didn’t pay much more than what a typical high school grad makes. This 24 million represents a full 40% of college grads in the workforce, a large group which had not realized the full professional or financial benefits enjoyed by other graduates. (These numbers include all workers with Bachelor’s, including those with graduate and professional degrees.) And while some job types have changed to demand high skills and a college degree in recent years - such as manufacturing and public administration positions - these are higher paid and do not negate the trend towards underemployment in lower earning non-college jobs.

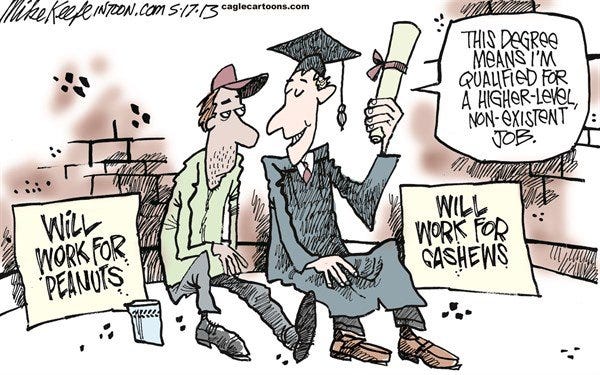

The results force the question: if there isn’t enough employment demand for college grads, shouldn’t we shrink college enrollment somewhat as a policy goal? If many trainees in plumbing aren’t finding work as plumbers, we’d decrease the training spots to be fair to the students, right? Why wouldn’t this simple logic apply to Bachelor’s degrees?

But this glut isn’t having a significant impact on individuals or policy. Students are probably not yet hesitating to enroll. And policy, driven by government, NGOs and higher ed, continues to press on the accelerator, urging college on everyone.

Personal choices

Individuals could act on their perception that the post-graduation jobs landscape is weaker and riskier by not enrolling or by requiring a reduced price.

The number of undergrads has been sinking ever since the “peak college” year of 2011. Until COVID arrived, that decline was driven by older students. Older students’ college decisions are often believed to be tied to economic conditions, a connection that held up well during the Great Recession and the subsequent economic recovery, but it is unclear if the market for college grads specifically influenced their declining attendance, rather than other market developments. As for younger prime age 18-24 year old students, the sagging college grad outlook did not discourage them, and their enrollment increased steadily in the 2010s.

The open question is what the sagging enrollments since 2019 signify. A year ago, we expected the 2021 admissions cycle would see a boom in both prime age and older students’ applications and enrollment. That may still happen - the country is just emerging from the pandemic - though initial signs aren’t promising. Anecdotal evidence voicing growing doubts from students and their parents about college’s value proposition is also out there - but is it just griping or a real, emerging change in perception?

Underemployment can also have an impact on college pricing - if something is less economically valuable, customers will want the price lowered. After a decade in which individual colleges on average were not able to raise their prices by even as much as inflation, last week, the Bureau of Labor Statistics report on consumer inflation flashed the lowest college tuition inflation in recent history. Although college pricing isn’t tied closely to post-career earnings, it correlates strongly with the income of families led by degree holders and so is indirectly affected by college grad underemployment. The lower pricing of course could also flow from an oversupply of college seats and the latest NACAC list of colleges with open spots does have some surprising names, exhibiting this excess capacity. So hesitations about college may be emerging from flattening prices but parsing it from other influences is difficult.

None of these signals are unambiguous. While there are some indications that individual students are shying away from college based on shifting perceptions, a cloud of other factors make any conclusion impossible. It’s fair to say that the deteriorating prospects of college grads had, prior to COVID, at most a minor impact on college attendance. TBD.

Policy

If underemployment among college grads is common, why would government push to expand college enrollments? Even if the labor market for high school graduates is poor - and it is poor - college enrollment doesn’t solve the problem. An individual may wish to enter the competition despite the odds, get a degree and take a shot at climbing on a college career track, but policymakers can’t reason this way.

This is a business blog but we are going to make some broader points here because certain conceptual mistakes recur over and over again in so much commentary pushing for increasing college attendance.

Statistical misunderstanding

“Graduates typically benefit from college” does not equal “All students should go to college.”

Almost all discussions of career outcomes after college talk in terms of averages. But more attention should be paid to distribution of outcomes, the variance. If college grads benefit on average, but a significant minority (40%!) don’t see any sizable career or financial advantage, the entire college journey should be viewed as a calculated risk, not a guarantee of prosperity.

To pick on an example, this Brookings release is unusually forceful — “All of it points to one conclusion, to quote Richard Reeves: ‘go to college’ “ — drawing conclusions exclusively from the median or average without considering the variance of results. It is disappointing to see an institution like Brookings indulge in errors like this. Let’s say this: if you are a 17-year old reading Brookings papers on labor economics and the rewards to college grads, you absolutely should go to college. But that lesson doesn’t necessarily apply to everyone else.

College isn’t just about economics, but higher ed policy is

College is not only a path to a better career, it also personally enriches students and many students enjoy college residential life. Individuals attend for these non-economic reasons, and that’s perfectly fine. But that can’t be the justification for a pro-higher-ed enrollment policy by government:

Many people find yoga personally enriching. Government is not subsidizing yoga and advocating greater participation in it.

Many people enjoy going to bars and hanging out. Government is not subsidizing bars and encouraging social drinking.

The case for public support of higher education rests solely on “worker preparedness” - career outcomes. It isn’t that the two above are irrelevant, but they are not among the policy goals.

Confusion about growing enrollments and the economy

Public good: One general argument argues that more people attending college is a public good, that it benefits everyone and helps the US economy. But this generality doesn’t apply to the practical question we face today.

Everyone believes a higher ed system should exist in the US and that some students should go to college. This helps all of us. That question isn’t under debate and isn’t relevant. The real question being debated: “is there a public benefit to enrolling 16 million students rather than 15 million?” (Picking two relevant numbers.) Given that this extra million will include many noncompleters and an outsize number of underemployed grads, any public good benefit is purely speculative and, given the Fed metrics, suspect on the face of it. A simple question: if those extra college grads will contribute so much, why are a third of grads in the workplace in jobs that don’t require college?

More of something good is better: Another widely-held principle is that the more educated the workforce, the better. High school dropouts fare worse in the labor market than those with diplomas who in turn fare worse than those with Bachelor’s, etc. Why shouldn’t this principle apply here and justify encouraging college enrollment? Because college students are adults, not minors, and can hold jobs. And because high schools teach minors a fundamental set of knowledge that forms a base level of learning for a functional adult. Colleges teach specialized skills beyond that base level to adults and an adult’s decision to acquire those skills is influenced by cost and benefit. As young people cross the bridge from childhood to adulthood, the way they approach educational decisions also transforms.

Cynical aside: When supply increases beyond demand, prices drop. Who provides the demand for college grads? Employers. Who benefits from price (wage) drops? Employers. So who profits from increased college enrollments? Cui bono?

Fighting inequality: this line - that sending more people to college will decrease income inequality - is hard to evaluate because coherently stating the case for it is difficult. How does enrolling more college students actually combat inequality? What’s the mechanism?

The position sometimes seems to assume all college grads magically have a college job created for them on graduation. That is obviously not the case.

Increasing the number of college grads would probably decrease middle class earnings, so it might compress the earnings gap between the middle class and lower income Americans. But that isn’t the sort of inequality being combatted.

Concerns about inequality center around the 1% and in particular the super-rich. Would the senior management of the Blackstone Group earn less because more finance majors graduate? The question answers itself.

Does more education encourage entrepreneurship? This argument needs to be supported by research, but entrepreneurship levels have been dropping in recent years while the ranks fo the college educated grew, and many businesses are started by people without degrees.

The cynical aside above actually argues exactly the opposite: more college enrollment benefits employers - often ultimately owned by rich individuals - and widens inequality.

This summary of research from the Washington Center for Equitable Growth comes to the same conclusion - that increased college enrollment cannot reduce inequality - based on a whole series of economics papers. Recommended.

Final thoughts

Despite all the rhetoric about how college attendance is necessary and represents a solution to the nation’s employment ills, a long-standing metric tracked by the New York Fed — one of the most reputable government research outfits — puts the entire case in doubt.

On an individual basis, high school students just beginning their adult lives deserve a more balanced and realistic messaging and should not be fed deceptive nostrums about college always leading to a better life. A fairer line would be: “college often leads to higher earnings and a more stable career, but there are risks and a significant minority of graduates as well as many college drop-outs suffer from their decision to enroll.”

This 2020 article by Michael Horn and Bob Moesta takes a wise, balanced tone.

This 2018 NPR story reports on training shortages in skilled blue collar occupations in the state of Washington and shows how higher ed messaging and policy are harming the economy and keeping many people from skilled, often well-compensated jobs.

On a policy level, arguments for increasing college enrollments need to be stated clearly, with detail and supported by facts. There is too much glib shorthand in NGO papers and the trade press, shorthand that conceals poor reasoning and a lack of factual basis. Unfortunately, promoting college enrollment is probably better understood as pure special-interest pandering by government and politicians. But its weak conceptual foundation is worth underlining.

We have not covered each and every one of the arguments for increasing enrollment, such as how college makes for a better citizenry - an absolutely toxic line of thought - or the often subconscious way “our culture represents your educational ability and accomplishments as synonymous with your human value”. (That last quote comes from Freddie deBoer - we recommend readers acquaint themselves with his writings on education, such as those found here and here.) There are many other views on this complex topic but let’s at least come to the issue with accurate information and clarity about what we are trying to achieve.

You can also read this post and others at our CTAS website.